“It is said that one should not dream when under anesthesia,

but I dreamed.

I dreamed of oranges.

Though the Swedish language fumbles in translating “awareness”

/consciousness / attention / conscious / oblivious –

I was aware.

I remembered.

The language gestures towards an unintentional vigilance, a perceptual awakening amidst intended forgetfulness, an oblivion “without” and “feeling,” in the absence of reality.

If everything were simple, one could tie “awareness” to a description of forgetfulness, “without” and “feeling,” in the absence of reality. But nothing is ever simple; complexity arises with the specter of memory. It has been shown that there are those like myself who have definitely been awake during anesthesia but do not always remember afterward.

Furthermore, memories can be defined differently. The dream is a rift between the conscious – the explicit memory images – and the unconscious – the implicit echoes.

I remember my oranges, oranges with the color orange. My orange-colored oranges, a color that didn’t exist in the English language until May 4, 1502. In Swedish, we started using “orange” sometime in the late 1600s, imprecisely.

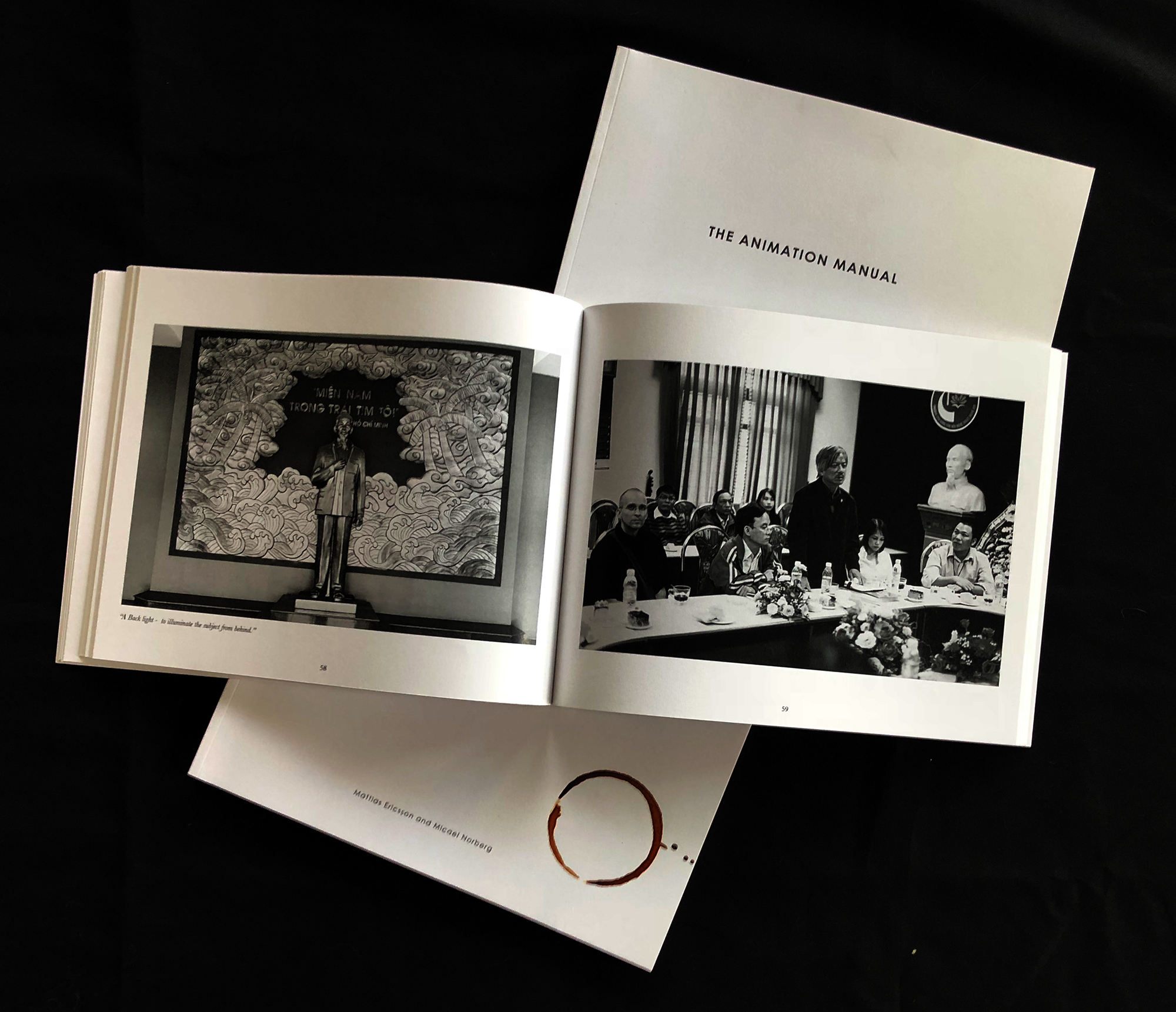

My oranges are a photographic image.

They dont taste. They are imprecise,

/ capturing reality / imprecisely /.

They are just a memory.

As if a photograph ever could capture something,

as if a photograph could represent reality.

My gaze through a camera lens

a gaze to see and be seen in reality.

there are always three parts in a photograph.

/ looking / being looked at / seeing /

Reality, realism

aiming for a stance,

emphasising the representation of things

as they are,

without idealization or distortion,

in a sensible way.

The camera is a sensible tool.

In a sensible reality,

the reality that exists independently of our perception or belief about it, realism strives to depict life, situations, or people truthfully, focusing on everyday life and ordinary people.

Am I being realistic with this image?

Traditionally, photography is obsessed with a realistic representation, striving for exact depictions of the physical world.

Imagine using the camera to find the subtle, almost unnoticed elements existing in the spaces between objects, thoughts, and experiences, the indeterminate space between things often overlooked but crucial in shaping our perceptions.

would that world exist?

Language constructs our understanding of the world; what if photography could do the same, telling more about reality and all the things I don’t understand, rather than idealized or imaginative subjects about everyday life.

A life we all live with sensibly?

Everything becomes a prefix,

an “un.”